When using the term ‘atypical employment’, ECA refers to all forms of relations between an airline and a crew member for the provision of work that is not in the form of direct indefinite employment - including, amongst others, self-employment, fixed-term work, work via (non-regulated) temporary work agencies as well as zero- hour contracts and pay-to-fly schemes.

Atypical employment is not necessarily illegal, but it can have a detrimental impact on health, safety, pay and working conditions. ECA believes that any form of contract in aviation that restricts commercial airline pilots from performing their jobs without burden (without feeling forced or feeling dependent in the operational choices they make) constitutes a safety hazard.

The majority of the self-employed pilots work for a low fare airline. Yet self-employment is mostly used to disguise what is in reality regular employment. In addition to the extremely precarious situation in which false-independent pilots are placed, this also creates an unfair competitive advantage for those airlines who use it and therefore severely distorts the aviation market.

ECA’s position is that the current EU legislative framework is unfit to provide aircrew sufficient labour, social and employment protection. ECA advocates for specific EU legal instruments to close the current legal loopholes, to create legal certainty for aircrew, airlines, and national authorities alike, and to allow for an effective application and enforcement of rules. For many years ECA is banging on the door of the European legislators (incl. EASA) but it’s hard to get positive response and follow up. This worries ECA because it puts both flight safety and the working conditions of the so- called group self-employed pilots at risk.

To become a pilot, students must pay high fees (from 50 to 100.000 EUR+) for getting a pilot’s license. After graduating from flight school and receiving “frozen license”, they are often asked to pay to learn the specific instructions to operate the specific type of aircraft that their employer uses (« type rating ») (from 20 to 90.000 EUR). Such situations are called pay-to-fly.

The trend to make pilots pay to learn how to use the specific type of aircraft of the employer is questionable from a labour law perspective: it can be argued that in some situations this may be a breach of European law. Moreover, though training bonds for type-rating (where payment for training is done by employers with the obligation for pilots to work in the company for a minimum period of time) are legal in some Member States, the conditions of training bonds are different and are sometimes misused, which can amount to pay-to-fly.

Another trend developing, in some countries, concerns schools selling technical qualifications to certain pilots at a notoriously inflated price. The school puts forward its ‘partnership’ with certain companies which get financial benefits from the partnership. While being a third party to the contract between the pilot and the school, the airline agrees to ‘host’ and pay (a small fee) the young pilot to gain experience, receiving income indirectly through the partnership agreement with the school. This advertising ‘promise’, never contractually agreed, serves to justify the exorbitant price of training and is, at least indirectly, akin to pay-to-fly.

Several situations can be distinguished and ECA’s view on that:

To guarantee fair and equal opportunities to access the profession, EASA must review and improve training standards and ban agreements between schools and operators unless type rating is fully provided and sponsored by airlines.

EASA, the EU, and the Member States must clarify the obligations of operators regarding the funding of the type rating and on the job learning to guarantee independence of the pilots when exercising professional judgement, and to avoid financial exploitation.

Furthermore, ECA endorses the attempts to get more clarity of art. 13 of the Directive 2019/1152 and asserts that different types of training should be the sole responsibility of employers, and that trainings bonds in that respect should not be possible anymore.

Many European pilots work on (bogus) self-employed contracts. While self- employment means providing services on its own without control from another party, bogus self-employment refers to business activities where the so-called self-employed person in reality is subject to managerial and proprietary tasks and is conducting independent business only on paper. It is highly questionable if a pilot can work as self-employed, given that he receives a duty roster every month and given the safety, administrative and liability requirements for persons flying on their account in commercial civil aviation.

This employment practice results in tax and health insurance savings for the «user» airlines while causing a loss of social security income to Member States and a net loss of rights for the workers: precarity, difficulty to exercise professional judgement, dependency towards employers, no social protection, no trade union recognition, no right to collective bargaining, non-application of the employment and social regulations. European Member States do not agree on a definition of bogus self- employment. In a very mobile profession such as aviation, these differences allow employers to bypass national laws which tackle bogus self-employment.

Bogus self-employment is often combined with complex social and labour engineering where intermediary organisations, sometimes even outside the EU, illegally hire out pilots and cabin crew to user companies. Intermediaries between bogus self-employed crews and user airlines bypass social and labour legislation on temporary agency work. This practice further complicates the possibility for aircrews to claim their rights.

EU legislation must define the notion of commercial crew member, clarifying the factual need for a direct employment relationship which includes the notion of subordination to the airline whilst remaining free to exert professional judgement.

EASA must clarify the safety obligation for airlines to employ sufficient pilots directly or through temporary work agencies accredited in the country from where the pilots work.

The EU must establish a refutable presumption of direct employment in aviation and extend temporary agency work protections to the self-employed.

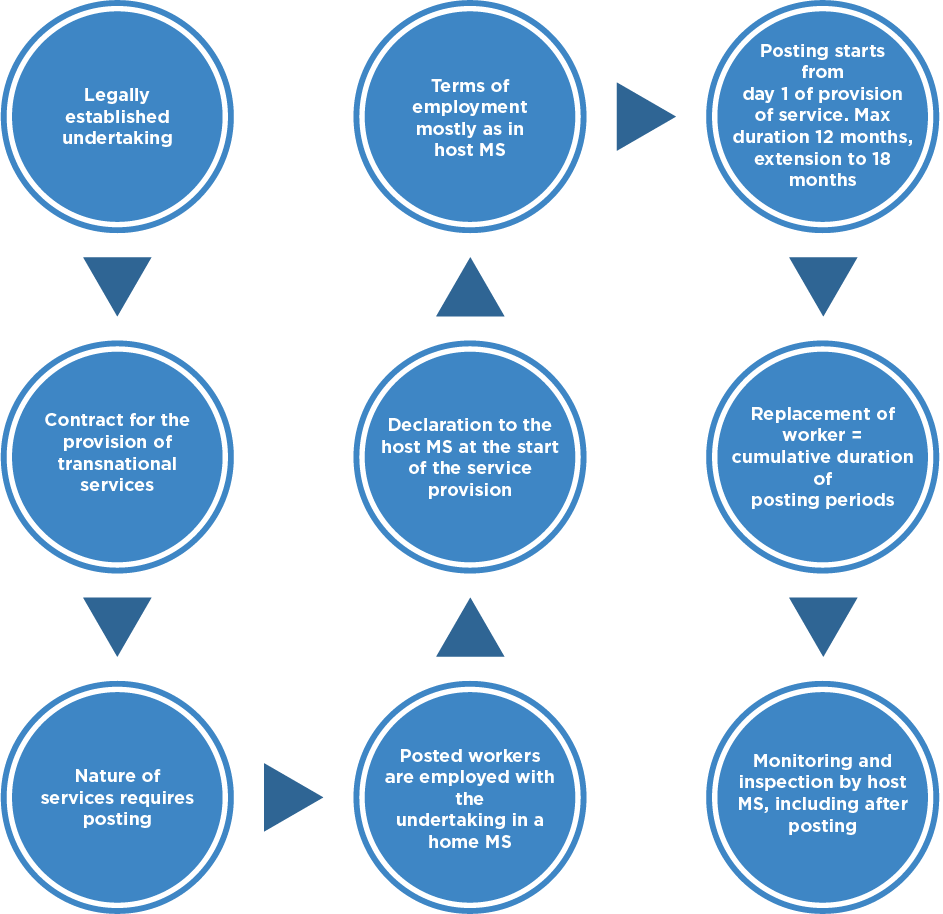

Airlines do not apply posting rules, when they should be doing so, to aircrews assigned temporarily (medium or long assignments) or permanently to operational bases outside the airlines’ principal place of business. Authorities do not enforce the posting rules either. New business models, low cost and ACMI (wet leasing) exploit this legal loophole to save money to the detriment of aircrew’s rights and working conditions.

Different reports, notably provided by the subgroup of experts from the European Commission and the Social Dialogue Committee on Civil Aviation show a high level of incertitude and divergence on the use, knowledge, applicability, and enforcement of posting rules to aircrew.

According to the EU, law on posted workers is generally regarded as a targeted effort to regulate and balance the following two principles:

Creating a level playing field for cross-border service provision in a way that is as unrestricted as possible

Protecting the rights of posted workers by guaranteeing a common set of social and labour rights to prevent unfair treatment and

the creation of a low-cost and precarious workforce.

The lack of a uniform application of posting rules for aircrew breaks this difficult balance between the airlines’ rights to provide freedom of service and the protection of workers’ rights. It creates social dumping and unfair social competition. Considering the data and recommendations provided by experts, the EU must act and propose adequate legislation to ensure a balanced situation where airlines can make full use of the opportunities of the aviation internal market and workers are treated fairly and their rights being respected.

The European Commission needs to clarify the application of posting rules to aviation in a specific legal instrument adapted to the mobile nature of the aircrew’s work.

Member States shall duly implement posting rules in their respective legislation.

National labour authorities shall be aware of workers from other countries who are working on medium or long-term assignments in their countries or of successions of different workers who, in the end, through their succession, come to occupy a permanent job in the host State. To this end, the EU must develop specific rules facilitating inspections, giving authorities access to employment documents - such as contracts, work schedules and home base - and allowing for the swift identification of the law applicable to each crew member at every moment.

The EU legislators, with ELA expertise help (European Labour Authority) must create specific instruments to identify, prevent and stop abuses from complex social engineering setups involving different countries.

Flights from Operational Bases Outside of the Airlines’ Principal Place of Business

The right of establishment is a pillar of the EU Treaties allowing airlines or any undertaking to choose the place where they want to establish their principal place of business. It also allows companies to operate in a stable and continuous way from operational bases in other countries.

Because of the mobile nature of aviation, and to reduce its costs, some airline employers falsely apply the same law to all their workers, even to those operational bases outside of the principal place of business. The EU and the Member States must ensure the application and enforcement of the laws and obligations of the country where the operational base is located. The lack of clarity on how this principle applies to aviation results in flags of convenience, forum shopping and social dumping.

An airline’s decision to provide air services from one airport on a stable, habitual, and continuous basis implies opening an operational base. The current legislative framework (Regulation 1008/2008) has contributed to the confusion about which law applies to airlines’ bases outside the country of the principal place of business. Indeed, Regulation 1008/2008 says that an airline with an EU operating license does not need additional authorisation to operate in another Member State. However, the EU-wide validity of the operating license does not exempt the operator from the obligation to comply with the local legislation of the country where they open an operational base.

The lack of a clear framework makes the enforcement of EU and national laws in the operating bases outside the airlines’ principal place of business difficult. This is especially the case regarding employment, social and labour regulation.

The EU must define the concept of “operational base” to clarify the applicable legal framework and facilitate the work of the national authorities when monitoring and enforcing national and EU legislation. Member States must be informed when an operational base is set up in their country.

Airlines owned or controlled by non-EU nationals who, under the combination of traffic rights can establish operational bases in Europe, must also follow the obligation to respect domestic law when operating from those bases.

Regulation 1008/2008 must define operational bases and clarify the airlines’ obligation to follow the laws of the countries where they open operational bases. 1008/2008 must establish mechanisms to ensure that both the authorising and the receiving states share information about the authorisations to open operational bases in other countries and that airlines follow local obligations.

The EU must propose and adopt a specific instrument that allows correct application of the EU social and labour acquis to aircrew.

The EU must be clear that EU and national law apply to non-EU airlines when employing aircrew and other operational staff in EU operational bases.

For more than 15 years, EU decision-makers have repeatedly been called upon to act on the social challenges in the European aviation market and their negative effects on aircrews’ working conditions. These challenges and effects are well known to these decision-makers, yet the different EU Transport and Employment Commissioners have systematically relegated them down on their agendas and then regretted not having sufficient time to address them at the end of their terms. Every legislative term, as Sisyphus, aircrews start again exposing the social challenges that erode their profession, their rights and their working conditions, and which ultimately undermine fair competition within Europe’s aviation market.

There is consensus amongst all experts on the need for action to stop abuses and guarantee fair (social) competition. The situation of mobile staff in civil aviation is similar to the road drivers’ one. In that case a mobility package was adopted to address the social concerns of drivers and to guarantee fair competition. The EU considered it as a necessary and proportional action. The EU must be coherent and address the legitimate concerns of workers and operators in the aviation sector swiftly.

In general, this means that ECA believes that any form of contract in aviation that restricts commercial airline pilots from performing their jobs without feeling forced or feeling dependent in the operational choices they make should be banned.

It is now urgent to design a legislative plan that considers specifically this problem. ECA is proposing concrete solutions. The status quo is not an option. Failure to act is a denial of social justice to a whole category of workers and a failure to the EU citizens.

January 2024

ECA - Industrial Relations Manual 2022.

Subgroup on social matters related to aircrews: paper on self-employment 2020.

Ricardo study on employment and working conditions of aircrews 2019.

LSE study: European pilots’ perception of safety culture in European aviation 2016.

Atypical employment in aviation (Ghent study) 2015.

Subgroup on social matters related to aircrew: posting of workers in CAT 2023